Miles from Welcomer is one of my favourite songwriters and mixing his EP really inspired my writing and my musical outlook. I was honoured when he asked to write something around the release of the new album. I love the idea of us musicians interviewing each other on our own platforms and I’m excited to share this. Keep an eye out for Welcomer’s new album coming soon…

If this country has a tower of song, I’ve always imagined Lake sharing a room with someone like Anthonie Tonnon. The songs are so heavily rooted in this place that you’d think they wouldn’t work anywhere else (at a quick glance I can count at least 20 Lake South song titles directly referencing place names).

But where Tonnon writes like your local historian, Lake comes at it something like the union leader. His voice straining, as he laments a home beset with a ‘neverending nightmare’ cost of living crisis.

Nowhere is this tub-thumping clearer than on his new record ‘We lived our lives on top of this’. Lead single ‘Auckland (so close to nothing at all)’ straight up just plays out a speech by Barry Pateman. Meanwhile Lake promotes the new E tū Musicians Union with his platform, meeting with Ministers and submitting to Parliament.

Politics and heart-ache are symbiotic here. The strength of Lake’s songwriting has always been in how he deftly discards trends and embarrassment, clearing the stage for the emotional heights of songs like Holloway Road or Brock & Dundas (Debt/Doubt). At his best, this results in songcraft fit for the tower: Anticoagulant (Getting Used to It), If You’re Born on an Island The Ocean Heals You.

Of course, that’s not to say the equation is perfect (cc bongos, a saccharine lyric here and there) but these moments become endearing when the overwhelming whole is so compelling. This is especially true in the live forum where his lyrics hit hardest (‘Another temporary job come to an end and I’m questioning if I’m worth a buck again’), backed by some of the capital’s best instrumentalists – friends Lake has made during his more than 2 decades in the game.

With album 4 out now, I’m pleased to put some proper questions to Pōneke’s underrated songcore lifer.

Kia ora Lake,

You’ve been writing songs for decades, investing time, money and annual leave on this project without a hope in hell of getting it back. What keeps you going?

Is there really no hope of getting it back!? Don’t tell my family that.

There is nothing like the feeling of writing a song that you believe in. It takes you out of yourself. It lifts you up. You finally understand. You can comprehend your place in the universe. It’s equally beautiful and powerful.

But as I say to Tim, it’s a mug’s game. The music industry is just part of the capitalist machine and as people internalise neoliberal values it becomes difficult to get out of the mindset of hard work = individual success.

People work so bloody hard at things. And they sacrifice so much for their work. Then when they succeed they think they deserve it. They worked harder than all those other people working their asses off and that’s why they deserve their multiple houses and nice cars. But 99% of people never ‘succeed’ at art in the way that they, or society, view success.

In competitive contexts many have merit but few ‘succeed’. What separates us in life is luck (or privilege).

If people know my work they’ll know how much I love running. I don’t go running or do exercise for any external benefits like weight loss or muscles or whatever. I run because I love the feeling of it. I love running up hills to see what’s on the other side. To get a new perspective on shit. Sometimes I struggle to leave the house but I know I’ll feel better for it.

Same with music. If we start making music for external benefits we will ultimately be disappointed. I make music for those moments of bliss. The hard thing is trying to give yourself as many opportunities as possible to do it. Sometimes that means chasing a review or a blog or funding or whatever.

Life is not a competition, helping others is not a weakness. Neoliberalism’s friend meritocracy is false and believing in it encourages selfishness, discrimination and indifference to the plight of the unlucky.

We don’t deserve success for our hard work. What we deserve is to be safe. To have food and water. To have shelter. And we all deserve unconditional love as human beings.

Touring and making records is expensive! You’ve spoken about the financial pressures facing musicians in Aotearoa today – can you let us in on how you manage to finance Lake South? Is it true that you play in a popular sea shanties group?

I’ve done a lot of jobs in my life. Apart from music (22+ years?), my longest job had been less than a year until recently… But I have a 3 year old and a steady job now. I live in hope that music can at least sustain itself financially but that’s tough.

The shanty band was inspired by my friends Croche Dedans from Nantes. I taught English badly there for 9 months and found a sea shanty choir through Couch Surfing.

I thought there must be some NZ shanties here and wanted to try and facilitate a sea shanty singalong group in Te Whanganui-a-Tara. My mate Vorn played the squeeze box so we hooked up a semi-regular thing at San Fran in 2012.

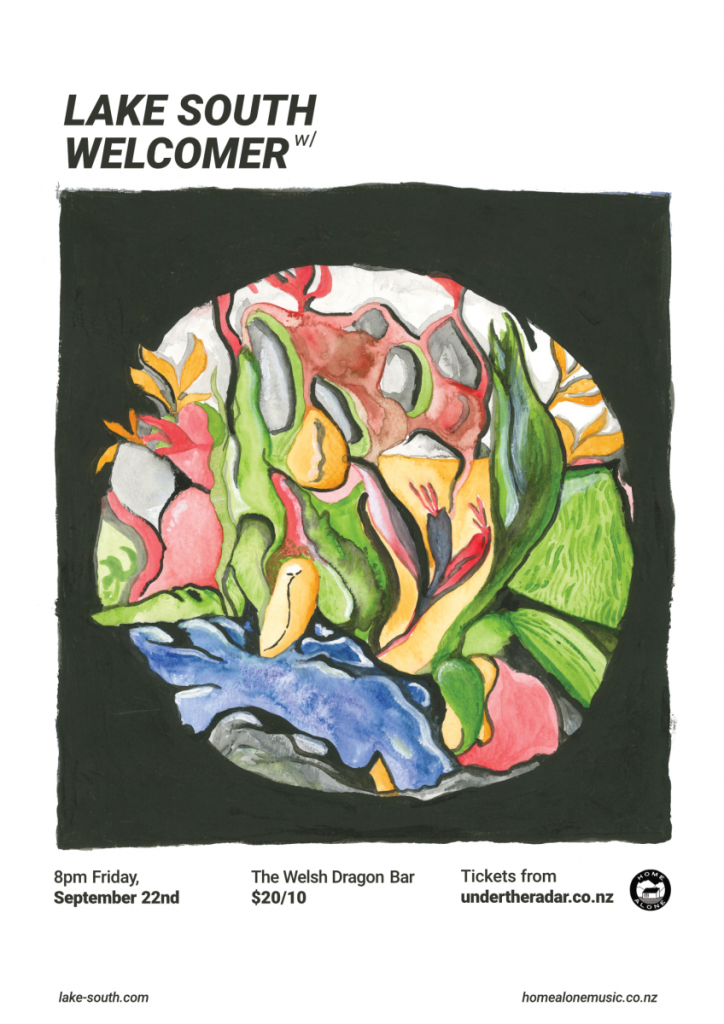

As happened to my French friends, the meet-up slowly morphed into a band. Though there is now a shanty meetup at the Welsh bar which is cool to see.

What started as a light-hearted way to learn some local folk songs has become quite a big part of my life. I love hanging out with the guys in the band and I learn so much from them musically. There’s something meaningful and beautiful about getting a whole hall of people to sing together from the same songsheet.

We’re working on a punk-shanty album atm.

Let’s talk about practice. What’s an ordinary week on the tools for Lake the songwriter looking like? How does your songwriting process differ to.. let’s say, 23 year old Lake?

The band practices one day a week. Then I try and get in there one other day to work on technical stuff or practice my own parts.

Since having a kid it’s difficult to find time to write songs. I didn’t realise how much free time I had before!

23-year-old Lake probably thought that creativity was something you couldn’t plan or train for and when the lightning struck he’d bang out a hit. I bumped into a musician acquaintance the other day and it made me realise how much crap we hold on to as artists.

We write a lot of our myths when we are young and stupid and then we keep believing them despite having grown up and learnt so much. I think we associate being young with being creative and energetic and productive but often it’s that we just had more time and less responsibilities.

What my friend said was that we lose some things as we age, but we have all these new tools we can use to be creative or get stuff done or whatever.

People say you can’t learn a language as an adult but you’re so much smarter and have so many more tools at your disposal to learn something than you did when you were a kid.

Is there anything you would tell 23-year-old Lake about making music now?

Work on your craft. You weren’t brought up on the piano like all the rich kids. You never studied music. It won’t kill you to do a bit of study.

This new record leans more towards your electronic production than on ‘The Light You Throw’. Did you set out with that intention? How much of a vision do you have before setting off to make an album?

I actually thought this was more a ‘band’ album than ‘The Light You Throw’ but maybe you’re right.

I think when you make a no/low budget DIY album and you want it to sound a certain way, you end up spending a lot of time in front of a screen. I spent so much time mixing/producing this album. A lot of zigging and zagging.

The cost to bring other good people in is just so high. But if I count all the hours I spent on this, I might do things differently next time.

I normally have a vision and theme for my albums. This time it was way harder to be intentional because I was sneaking in writing/producing sessions around parenting my now 3 year old.

Learning how to make music and still be good to your family, friends and job was the challenge with this album. I’ve come to terms with things. I’ve learnt a lot.

When you write about this country it always seems like something between lament and love letter. With what feels like miserable headline after miserable headline and record numbers of (mostly young people) leaving (69,100 left in the year to February 2025) I can’t help but hear themes of resilience here. Looking back on these songs, what thoughts do you think you were wrestling with?

I always try to write fluidly between where I’ve been, where I am, and where I want to go.

I start with a place and what I was thinking then, and I jump back and forward from now to then. And I always want something to look forward to.

It’s true that Aotearoa and my place in it features a lot in my songs. There was a review of this album that said my songs were impenetrable and unrelatable because they were too specific and obtuse (my words). I respectfully disagree. It’s their specificity of place that makes them relatable. And it’s their allusiveness that gives you room to dream.

My friend Jean Phillipe (Croche Dedans) told me about the 3 deaths. We are children and innocent and then that part dies and we become adults (1st death). Then we’re adults and we’re free and we experiment. Then that part dies (2nd death) when we get responsibilities like families and houses etc. Then we actually die (3rd death).

Do you have a favourite song on the record?

Changes all the time. Today: To know this dirt.

Which song was the most difficult to finish and why?

I struggled with a lot of songs on this album because of the aforementioned newfound parenthood.

I guess there’s a reason why a lot of people give up music when they have kids!

This is what I wrote in my press release about that:

“Their fourth album was written in the pockets of free time in the 3 years since the birth of Lake’s first child. Immense joy, white nights, the mourning of a life lived lonely, and the delicate embrace of a love without limit.”

‘Can we hold this ground’ was just hard for me to sing the melody. And it goes places in the 2nd chorus that I wouldn’t expect it to.

‘Auckland’ was also difficult. It’s one of my favourites now but it was kicking around as 2 or 3 different songs for ages. I guess that’s why it’s got the key change.

How has music infrastructure in New Zealand changed since you got involved? Do you think something like a Nature’s Best compilation could even happen now?

Hmmm. I’m not sure. I’ve always been an industry outsider. Not through lack of trying! I’m working on having the confidence to talk to people more.

Nature’s Best? Totally. NZ only has the media and headspace for 20-40 artists at a time so that’s the perfect number for a double CD release.

What I am excited about is the E tū Musicians’ Union. As I said before, life is not a competition and helping others is not a weakness. I would love to see us work together as musicians for a better Aotearoa. With a united voice we can improve conditions and teach people the value that music has in our society.

You’re a founding member of Home Alone Records, a DIY label and community that has put out some beloved Pōneke projects by Mystery Waitress, Timothy Blackman, French for Rabbits and more. How has that community informed Lake South over the years?

Tim and Brooke are amazing people to work with. I feel so grateful to be a part of Home Alone. I think this relates to my comments above about working together. In our small way we can contribute to the music community and help people share their music with the world.